What is SOLID?

Taking as a referece the book “Clean Architecture” by Robert C. Martin we can say the following:

Good software system being with clean code. On the one hand, if the bricks aren’t well made, the architecture of the building doesn't matter much. On the other hand, you can make a substantial mess with well-made brick. This is where the SOLID principles come in.

The SOLID principles tell us how to arrange our functions and data, and the goal of the principles is the creation of mind-level software structures that:

- Tolerate changes

- Are easy to understand

- Are the basis of components that could be used in many software systems

Well, now we have an overview of SOLID, and now I going to tell you about each one of the principles that form part of SOLID, those are the following:

- Single responsability:

“A module should have one, and only one reason to change”

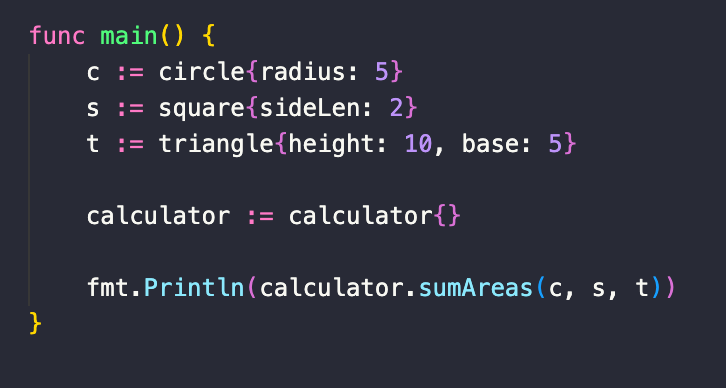

- Open-Close principle:

“A software artifact should be open for extension but closed for modifications”

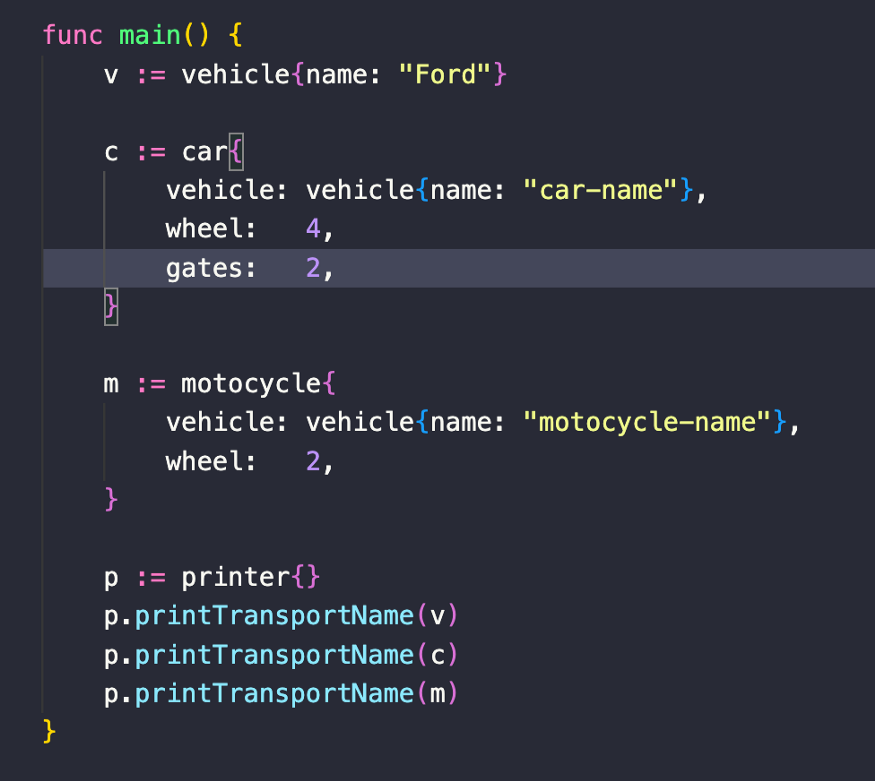

- Liskov substitution principle

“What is wanted here is something like the following substitution property: If for each object o1 of type S there is an object o2 of type T such that for all programs P defined in terms of T, the behavior of P is unchanged when o1 is substituted for o2 then S is a subtype of T”

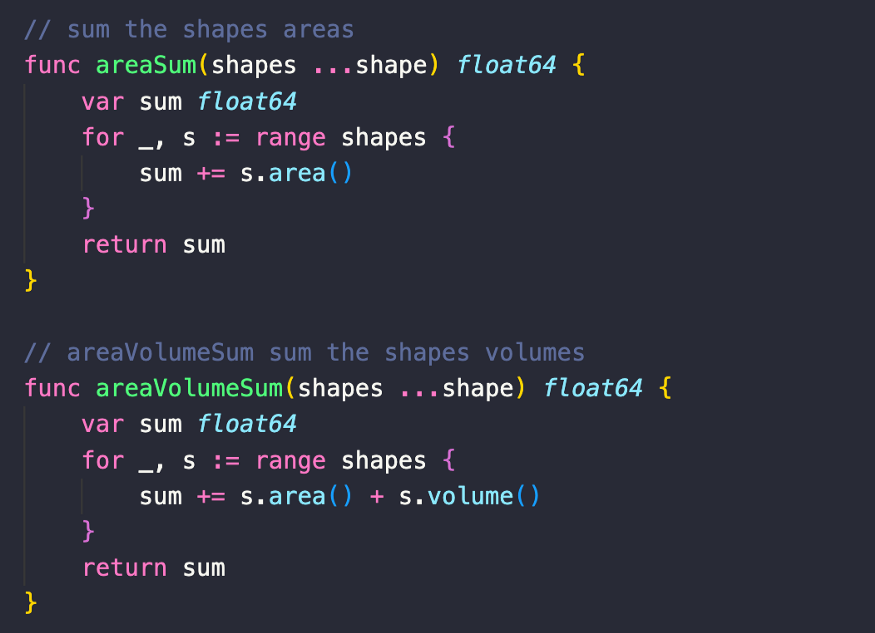

- Interface segregation

“Clients should not be forced to depend on methods they don't use”

- Dependency inversion

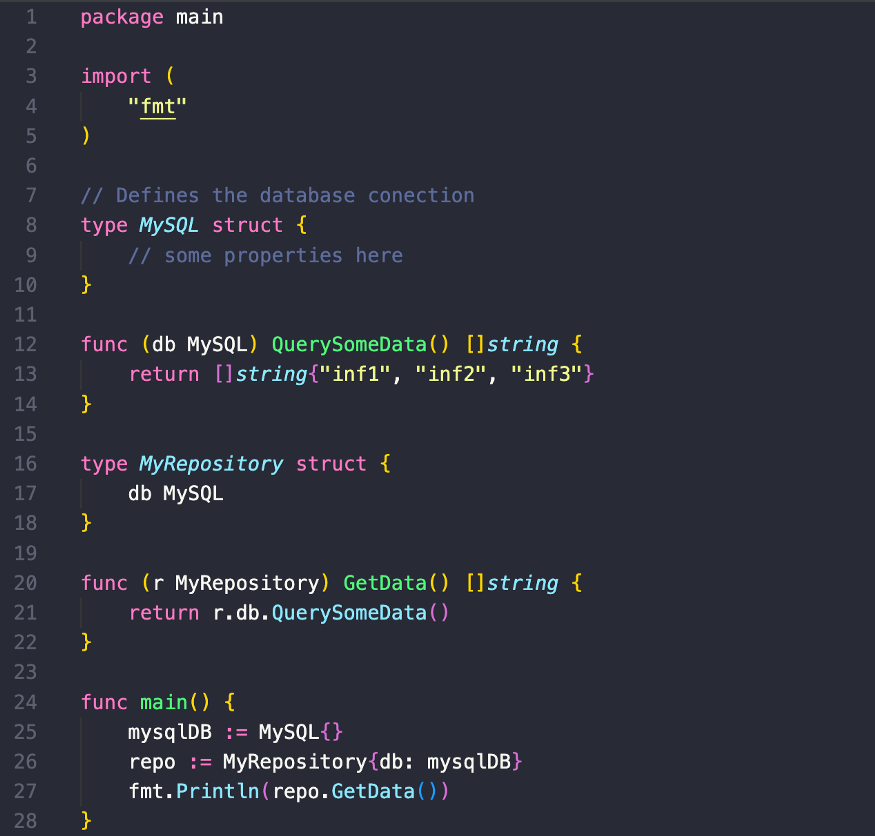

“High-level modules should not depend on low-level modules. Both should depend on abstractions. Abstractions should not depend on details. Details should not depend on abstractions”

We going to take base on each one of the principles in the next section.

Note: For more information about SOLID I recomend to read the book “Clean Architecture” by Robert C. Martin

SOLID and Go

As we can see in the previous section, SOLID is thought for Object-Oriented programming but that is not a limitation for languages like Golang and I will show you how you can arrange it and implement it in your Golang projects.

Let us start with each one of the principles and define how are implemented with Golang.

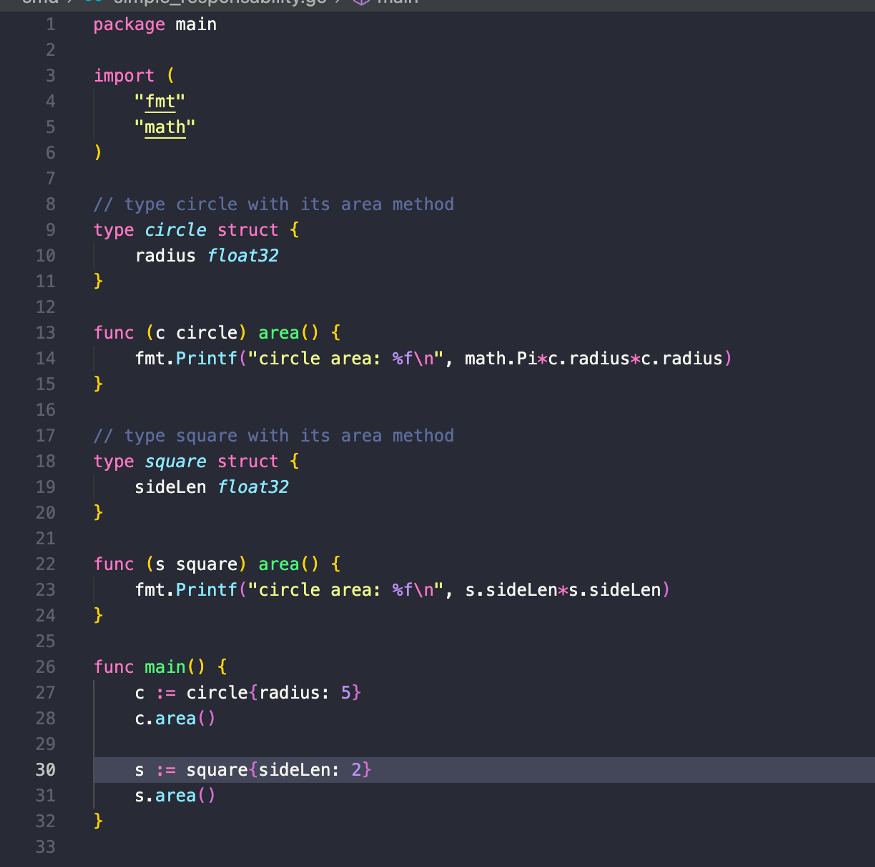

Single Responsibility Principle - SRP

— Definition: “A module should have one, and only one reason to change”