Let’s face it — Kubernetes gets ALL the love. Although Nomad is a GREAT product, it has a much, much smaller user base. As a result, there are fewer tools geared toward supporting it.

Can we get some Nomad Love Here?

Let’s face it — Kubernetes gets ALL the love. Although Nomad is a GREAT product, it has a much, much smaller user base. As a result, there are fewer tools geared toward supporting it.

One thing that is lacking in the Nomad ecosystem is tooling for managing Nomad deployments.

Believe me…I spent a looooong time time Googling far and wide, using search terms like “GitOps for Nomad”, “Tool like ArgoCD for Nomad”, “CD tools for Nomad”, and so on. I stumbled upon a post in this discussion which points to a list of CI/CD tools which integrate with Nomad. Unfortunately, the tools listed on there didn’t really fit the bill.

Having spent several months in late 2020/early 2021 neck-deep in Kubernetes and developing a deployment strategy around ArgoCD (I have a whole series of blog posts just on ArgoCD), I understand the importance of having a good deployment management (also known as Continuous Delivery or CD) tool for your container orchestrator. This is ESPECIALLY important when you’ve got an SRE team whose job includes overseeing the health of dozens and dozens of microservices deployed to your container orchestrator cluster(s) across multiple regions. IT. ADDS. UP. A deployment management tool like ArgoCD gives you that holistic system view, and a holistic way to manage your deployments.

At the end of the day, as far as I can tell, the only two big-ish commercial deployment management tool offerings for Nomad are:

- Spinnaker, an open-source tool which was developed at Netflix

- Waypoint, which is developed by HashiCorp

I was personally drawn to Waypoint, because, as a HashiCorp product, it means that it plays nice with other HashiCorp products. Most importantly, it can run natively on Nomad, as a Nomad job, just like ArgoCD runs natively on Kubernetes! Spinnaker, on the other hand, cannot run natively on Nomad.

Fun fact: Waypoint can also manage deployments to Kubernetes, and can run natively in Kubernetes. I think the Kubernetes features for Waypoint came out before the Nomad features.

Now, keep in mind that Waypoint is pretty new. It was first launched on October 15, 2020. The latest version of Waypoint, v0.7.0, was launched on January 13th, 2022. That’s pretty fresh.

So, is Waypoint up to snuff? Well, let’s find out, as we explore the ins and outs of Waypoint!

Objective

In today’s tutorial, we will:

- Learn how to install Waypoint on Nomad using my favourite local Hashi-in-a-box local dev environment, HashiQube.

- Learn how to use Waypoint to deploy a group of related apps to Nomad. This is very basic. I will not get into more advanced concepts like workspaces and triggers.

- Discuss Waypoint as a deployment management tool.

Assumptions

Before we move on, I am assuming that you have a basic understanding of:

- Nomad. If not, mozy on over to my Nomad intro post.

- HashiQube. It’s basically a virtualized environment that runs a bunch of Hashi tools together. I recommend that you mozy on over to my HashiQube post for more deeets.

Pre-Requisites

In order to run the example in this tutorial, you’ll need the following:

- Oracle VirtualBox (version 6.1.30 at the time of this writing)

- Vagrant (version 2.2.19 at the time of this writing)

Tutorial Repo

I will be using a Modified HashiQube Repo (fork of servian/hashiqube) for today’s tutorial.

Waypoint Installation Overview

In this section, I’ll explain how to install Waypoint. But don’t worry yet about trying these steps right away, because in the next section, Running the Waypoint Example on HashiQube, you’ll get to do it as I run through the steps of booting up your HashiQube VM and deploying your app bundle to Nomad using Waypoint.

During the Vagrant VM provisioning process on HashiQube, Waypoint is installed by way of the waypoint.sh file.

At the time of this writing, the latest version of Waypoint is v0.7.0. Please note that the Waypoint provisioning scripts in this example will always pull whatever the latest version is. If you want to lock that down, please update line 14 of waypoint.sh to:

With the Waypoint binary in hand, it’s time to install. This happens on line 23:

The above line will install the Waypoint server on Nomad (so that it runs natively as Nomad job). Since Waypoint needs a database to keep track of deployments, we must create a host volume in Nomad. I’m using MySQL as the host volume.

Note: You can use either a Container Storage Interface (CSI) Volume or a Host Volume to store the Waypoint Server’s DB. More details here.

We need to have a DB in place before running the Waypoint server installation, otherwise the install will barf out. This means that I had to deploy the MySQL DB during the Nomad provisioning process. During the Nomad provisioning process, I had to do 2 things.

First, I configured the host volume in the Nomad server.conf file. This happened in lines 40–43 in nomad.sh:

Note how my host volume is named mysql. This is the same volume name referenced in the nomad-host-volume flag of the waypoint install command:

I also had to deploy the MySQL database to Nomad. This happens at the end of the Nomad provisioning process, in line 140 of nomad.sh:

The Nomad jobspec for MySQL can be found here.

After installing the Waypoint server, you can see the job running on Nomad (http://localhost:4646):

Note: You can see that the mysql-server job is also running. Remember that this was deployed during the Nomad provisioning step.

You can also check to see that the waypoint-server is running using Nomad CLI:

Sample output:

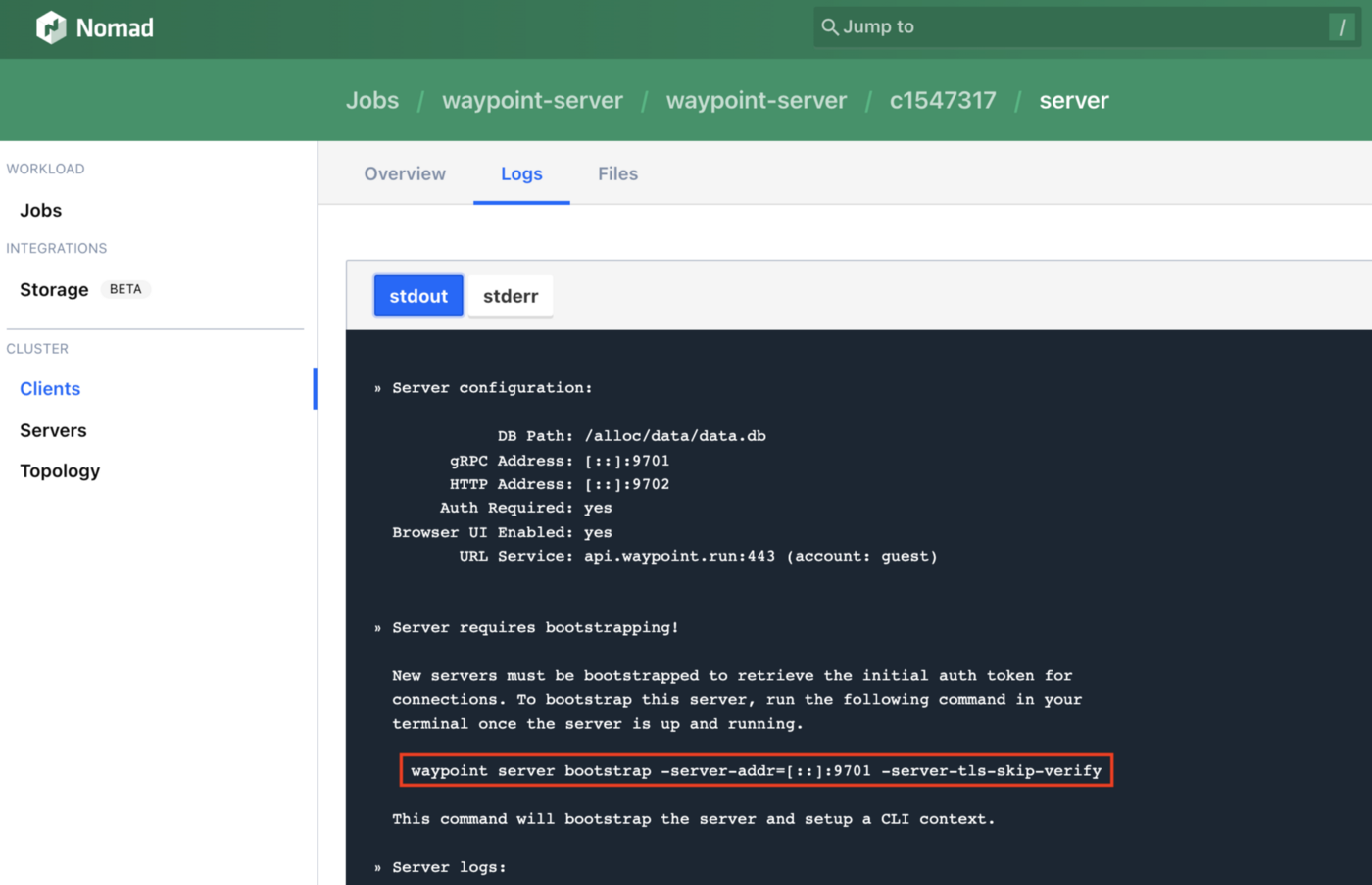

But we’re not done yet — we need to bootstrap the server. This happens on line 24 of waypoint.sh.

This is technically supposed to happen automagically, but for some reason it doesn’t (haven’t figured out why yet, so any suggestions are welcome). I found out about the above command from looking in the server logs of the Waypoint server job running on Nomad. Hope this saves you a ton of grief if you run into a similar situation!! 😊

Again, if you prefer the Nomad CLI (make sure you have jq installed):

Sample output:

Now that we understand how Waypoint is installed, let’s actually install it, shall we?

Running the Waypoint Example on HashiQube

Time to put things into practice by standing up our environment using HashiQube!

As a reminder, we will be using the tutorial repo for this example. It is a fork of the servian/hashiqube repo, and includes the following modifications:

- Uses Traefik instead of Fabio for load-balancing.

- Bootstraps Vault, Consul, Nomad, and Waypoint only.

- Configures Nomad to give it the ability to pull Docker images from private GitHub repos given a GitHub personal access token (PAT). This is optional (more on that below).

- Configures Nomad/Vault integration so that you can use Nomad to pull secrets from Vault.

Let’s get started!

1- Clone the HashiQube Git Repo

2- Docker plugin configuration

Note: If you wish to skip this configuration, simply comment out lines 46–52 and lines 74–87 in nomad.sh.

The nomad.sh file has some additional configuration which enables you to pull Docker images from a private GitHub repo. This is enabled in lines 46–52 in the docker stanza, telling it to pull your Docker repo secrets from /etc/docker/docker.cfg, which is configured in lines 74–87.

Line 79 expects a GitHub auth token, which is made up of your GitHub username and GitHub PAT. It pulls that information from a file called secret.sh, located at vagrant/hashicorp/nomad in the guest machine.

For your convenience, you can create secret.sh on your host machine like this:

Be sure to replace <your_gh_username> with your own GitHub username and <your_gh_pat> with your own GitHub PAT.

3- Install & configure up dnsmasq

Note: You only need to do this configuration once, and then you’re golden for all subsequent times that you bring up HashiQube.

I’m running all of my Nomad jobs locally (i.e. on localhost) on HashiQube. I’m also using the Traefik Host rule to configure my Nomad jobs. In a nutshell, this maps to a nice URL (*.localhost) running on port 80, regardless of what port the underlying service uses.

For example, the Traefik endpoint will be traefik.localhost, and (spoiler alert) the OTel Collector’s endpoint will be otel-collector-http.localhost.

Unfortunately, during my experimentation, after I initially set all this up, I couldn’t hit http://traefik.localhost. I kept running into this error:

What added to my confusion is that I could hit that endpoint on Chrome, Brave, and Waterfox, but not on Safari. This became a real problem when I tried to get my sample OTel tracing program to hit the OTel Collector endpoint and it kept giving me that dreaded Could not resolve host error. A deep panic set in. 😱

Fortunately, The Google saved the day, and I found the solution, by way of installing a tool called dnsmasq. For your reference, the post that saved me can be found here .I’m on a Mac, and the steps below saved my bacon:

a) Install dnsmasq

b) Configure

Copy the sample config file to /usr/local/etc/dnsmasq.conf, and add address=/localhost/127.0.0.1 to it

Restart dnsmasq services

Add a resolver to allow OS X to resolve requests from *.localhost

c) Test

Even though foo.localhost doesn’t exist, we should now be able to ping it, since it will map to 127.0.0.1, as per our configs above.

Result:

4- Start Vagrant

Now we’re ready to boot up our HashiQube environment. Make sure that you’re in the repo root folder (hashiqube), and run the following command:

Now wait patiently for Vagrant to provision and configure your VM.

Once everything is up and running (this will take several minutes, by the way), you’ll see this in the tail-end of the startup sequence, to indicate that you are good to go:

You can now the services below:

- Vault: http://localhost:8200

- Nomad: http://localhost:4646

- Consul: http://localhost:8500

- Traefik: http://traefik.localhost

- Waypoint: https://192.168.56.192:9702

If you look at the Waypoint URL above, you’ll notice two things:

- The endpoint is

https, nothttp. This is because the Waypoint UI only runs onhttps. - We’re using the Vagrant VM’s IP to connect to the Waypoint UI instead of

localhost, because it doesn’t work withhttps://localhost:9702(even though we exposed port 9702 in the Vagrantfile. My guess is that it has something to do with the fact that the Waypoint UI is usinghttps. Anyone else have any thoughts on this?

Note: If your Vagrant VM starts up properly, but you find yourself unable to access the Waypoint UI, it might be due to an IP address collision with another device on your network. This happened to me. I was happily using 192.168.56.100, and then suddenly, it wasn’t working anymore. I had to switch my Vagrantfile to use 192.168.56.192 (I randomly picked it and prayed it would work 😅), and then it was all good.

When you hit the UI, you’ll see a bunch of security warnings. Once you bypass all the warnings, you’ll see this:

Isn’t it pretty? 😃

Note: In a production environment, you will want to set up TLS and all that good stuff. This is outside of the scope of this discussion. But if you want some guidance on how to do this, DM

David Alfonzo, who got this working with TLS + Traefik.

5- Install the Waypoint CLI on your host machine

If your Host machine (i.e. the non-VM) is a Mac, you can install the Waypoint CLI via Homebrew like this:

While not needed for the purposes of this tutorial, you can also install the Vault and Nomad CLIs if it tickles your fancy:

If you’re not on a Mac, you can find your OS-specific instructions for installing Waypoint, Vault, and Nomad CLIs. Note that these are the binary installs for the apps themselves, and they also contain the CLIs.

6- Configure the Waypoint CLI

Now that the Waypoint CLI is installed, we need to configure it so that it knows to talk to the Waypoint server running on HashiQube. How do we do that?

During the Waypoint provisioning process of our Vagrant VM, in line 64 of waypoint.sh, we generate a Waypoint token:

And save it to a text file, per line 66:

This file is also accessible to the host machine at <repo_root>/hashicorp/waypoint/waypoint_user_token.txt. I’ve gitignored the file so that you don’t accidentally push it to version control. You’re welcome. 😉

Armed with a user token, we can login to our newly-provisioned Waypoint server via the CLI on your host machine. Remember that you must be in the hashiqube repo root in order for the line below to work.

Note: VAGRANT_IP refers to the IP address of your Vagrant VM (see line 26 in the Vagrantfile.

Sample output:

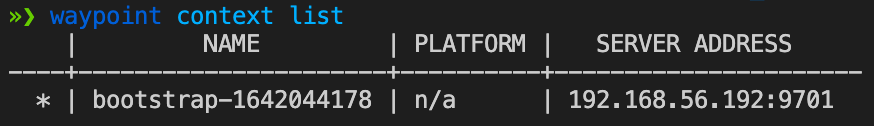

Logging into Waypoint for the first time creates a Context. A Waypoint Context is similar in concept to a Kubernetes Context — it represents a Waypoint server that you’re connecting to. If you need to connect to another Waypoint server, you’d simply switch the context before running any operations against that server via the CLI.

And in case you’re wondering how you can view your list of current contexts:

Sample output:

As you can see from the output above, the context name is bootstrap-1642044178. This name was auto-generated, courtesy of Waypoint.

If you want to use a specific context, you would run:

Where <context_name> is the name of the context you want to change to — i.e. one of the NAME values output from running waypoint context list.

If you wanted to create a context, you would run:

Where <waypoint_token> is your Waypoint token, and <context_name> is the name that you want to give your new context (it can be whatever you want).

In case you’re wondering where Waypoint stores your context, you can find out by running:

Sample output:

If I poke around at the config path listed above, I see a few files in there:

_default.hcl(points to your default Waypoint Context — it’s a symlink)bootstrap-1642044178.hcl(yours will be named the same as your Context name)

You may see more files in there than what I have — one per Context you’ve configured, plus _default.hcl.

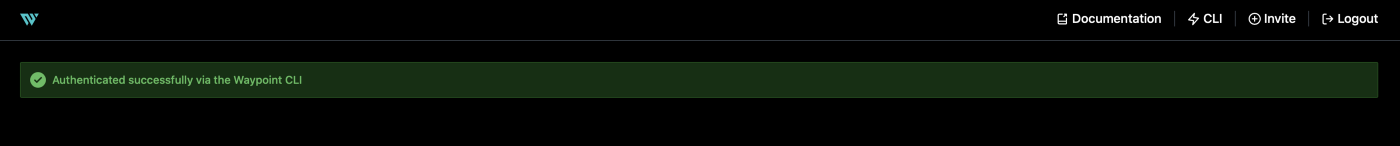

Now that you’ve logged into Waypoint via the UI, you can also do this:

This automagically auto-authenticates you into the Waypoint UI. Again, remember to bypass all the security warnings so that you can get to the UI:

Woo hoo! You’re in!

7- Deploy a project to Nomad using Waypoint (an example)

We are now ready to run a Waypoint example! If you’ve been following along in my blog posts, you know that I use my trusty 2048-game example. So of course I will use this app in the example here. Since Waypoint gives you the ability to deploy multiple related apps at the same time, I will demonstrate how to deploy two apps under a single Waypoint project. As you may have guessed, a project is a group of one or more related applications.

Note: Although the two apps in the example are not at all related, I’ve schlepped them together into to illustrate the concept of deploying two apps in the same project.

To run the example, let’s navigate to our examples directory (assuming you’re starting from the repo root, hashiqube):

The waypoint init command looks for a waypoint.hcl in the directory from which you run waypoint init. In our case, we were in hashicorp/waypoint/examples/sample-app, so Waypoint looked for (and found) our waypoint.hcl there. If Waypoint finds a waypoint.hcl file, it validates it to make sure that your HCL is well-formed and that you’re not trying to do anything funky and non-Waypoint-y.

If Waypoint doesn’t find a waypoint.hcl, it will scaffold a waypoint.hcl for you, which you can fill out to your heart’s content.

The waypoint init command also creates a .waypoint directory in the directory where your waypoint.hcl is located (make sure that you gitignore that directory, as I did in the example repo.

Here is our waypoint.hcl:

The waypoint.hcl file starts with a project definition. Per line 1 above, our project is aptly named sample-proj.

In the file above, we are defining two applications:

2048-game(lines 26–43)otel-collector(lines 45–61)

The label you use for the app stanza can be whatever you want — you can use uss-enterprise and battlestar-gallactica, if you want. Obviously, the more descriptive (with regards to what the app actually does), the better. 😁

In our example, each app definition has two sections: build, and deploy. We define how we want to build and how we want to deploy by using plugins. Waypoint has a bunch of canned plugins that you can use. You can also define your own. For what we want to do, we can use the existing canned plugins.

Let’s start with the build stanza.

The build stanza can do one of two things:

- Build a

Dockerfileand publish it to a given Docker registry - Pull a

Dockerfilefrom a given Docker registry

I don’t particularly find the first use case all that useful to me. In my opinion, building a Docker image and publishing it to a registry should be left to a CI tool like Jenkins, CircleCI, or GitHub Actions. A deployment management tool like Waypoint should pull an existing Docker image and deploy it to whatever target(s) I specify. Build once, deploy many.

Note: The CI tools listed above can also deploy to Nomad, Kubernetes, etc. That said, they aren’t well-suited for giving you a holistic view of your app deployments across multiple environments and clusters, like a deployment management tool would.

So, keeping in mind that we want to grab an existing Docker image to deploy to a specific Nomad environment, we use the docker-pull plugin, which includes the info you need to pull the specified Docker image and tag from a given Docker registry.

To deploy each app, I use the deploy stanza with the nomad-jobspec plugin. Waypoint supports two Nomad-native ways to deploy to Nomad: using the nomad plugin, and the nomad-jobspec plugin. The nomad plugin basically creates a Nomad jobspec on-the-fly based on a bunch of parameters that you set. Unfortunately, if you want to do anything more advanced (like using Traefik for load-balancing), you’re kinda screwed. Lucky for us, the nomad-jobspec plugin gives us more flexibility. This plugin lets you feed an existing Nomad jobspec file into Waypoint. YUM. That’s what we see in line 37–39 and line 56–58 of our waypoint.hcl.

Let’s look at the nomad-jobpsec config for the 2048-game app:

The above snippet says that we’re using a templatefile called 2048-game.nomad.tpl located at ${path.app}. The Waypoint variable ${path.app} is your working directory (i.e. where waypoint.hcl is located). The template file, 2048-game.nomad.tpl could very well have been called 2048-game.nomad, or 2048-game.hcl. The .tpl extension is just a convention indicating that it is a template file (i.e. we’re passing in some parameterized to that file).

So what parameters are we sending over to 2048-game.nomad.tpl above? It looks like we’re sending a parameter called docker_artifact, and that it’s getting its value from something called var.game_2048_docker, an object made up of an image field and a tag field.

If we look up at lines 3–12 of waypoint.hcl, we can see that it’s game_2048_docker is defined there:

This particular variable is of type object (i.e. a map), but you can also define variables of type string and number. More info here.

When we pass it to the template specified in the nomad-jobspec plugin, we reference it as ${var.game_2048_docker}, where var tells us that it’s a Waypoint variable. And we’re assigning it to docker_artifact as we pass it it into our template, 2048-game.nomad.tpl. If you look at line 37 of 2048-game.nomad.tpl, we reference docker_artifact like this:

Since docker_artifact is made up of an image field and a tag field, we reference the fields as docker_artifact.image and docker_artifact.tag, respectively.

Note: waypoint.hcl also supports a release stanza, but as far as I can tell, the deploy stanza takes care of the release part for us, since the Nomad jobspec takes care of the stuff that the release stanza is supposed to do, so it’s moot as far as our example is concerned. Please feel free to correct me if I’m wrong.

Now that we know what’s going on…let’s deploy the project:

Note: It’s typically a good idea to always run waypoint init followed by waypoint up every time you make a change to your waypoint.hcl. That way, Waypoint can catch any boo-boos in the waypoint.hcl file.

Sample output:

If we mozy on over to our Waypoint UI by way of waypoint ui -authenticate, we’ll see a new project called sample-proj:

If we drill down (by clicking on sample-proj), we’ll see that it’s deployed both apps in our bundle — 2048-game and otel-collector:

And if you click on 2048-game, you’ll see this:

According to Waypoint, the app has been deployed to Nomad! Let’s check Nomad to make sure that that’s the case by going to http://localhost:4646:

Unfortunately, if something goes caca with the Nomad deployment, Waypoint doesn’t tell you, which honestly sucks. When I compare to the fact that my beloved ArgoCD does that and more, it makes me sad. 😢

8- Deleting a project

If you wish to delete the apps deployed under your project, you can do so by running:

Sample output:

This nukes all apps in our project, so it means that the otel-collector and 2048-game apps are gonzo from Nomad. The Waypoint UI is not so great at showing destroyed deployments:

This section probably needs a little more love.

Thoughts on Waypoint

If you’re part of an SRE organization, you need a tool to manage your deploymens. Why? Because you need to have a holistic view of all the apps deployed across all of your container orchestrators — whether it’s Kubernetes, Nomad, Docker Swarm, or whatever else. Deployment management tools answer the following questions:

- What apps are deployed to what clusters?

- What apps are part of the same bundle (project)?

- Did any apps barf out at the time of deployment?

- Did any previously-running apps suddenly start to barf out?

- Do I have a good mechanism for rolling back my deployments?

So does Waypoint fit the bill?

Waypoint is a GREAT first step at a deployment management tool for Nomad. There aren’t too many such tools available for Nomad, and it’s nice to see that HashiCorp is throwing its hat into the ring and giving its own container orchestrator some much-needed love. ❤️

Having spent a chunk of 2020 and 2021 digging deep into ArgoCD, I’ve definitely been spoiled by its vast capabilities, and unfortunately, I don’t see many of the features I’ve grown to love from ArgoCD in Waypoint…yet.

As an SRE, here is my Waypoint wish list:

- Project deletion. Waypoint doesn’t currently support Project deletion, so if you want to delete a project, you’re outta luck. The only way to “delete” a project in Waypoint is to nuke your whole installation. Ugh.

- A holistic view of deployments. It’s awesome that I can see what apps are deployed as part of a project, but I would love to see a high-level summary of my deployments without having to drill down into each app in the UI.

- A dashboard of application health. When deploying a group of related apps (project), I’d like to see which apps were deployed successfully from the UI. Right now, I still have to go into Nomad to check up on the health of my apps. I don’t want to do that.

- Not being forced build step in

waypoint.hcl. To be honest, forcing me include abuildstanza all the time doesn’t make a whole lot of sense to me, because I deploy to Nomad using thenomad-jobspecplugin for thedeployphase, and as far as I can tell, in the Nomad deploy phase, it pulls the image from the Docker registry all over again. (Please correct me if I’m wrong.) Unfortunately, when I tried to purposely exclude thebuildstanza from thewaypoint.hcl, it caused Waypoint to err out onwaypoint initandwaypoint upwith the error'build' stanza required;. - Better documentation. I find that the Waypoint docs are a bit sparse. The code examples are just snippets, which makes it a bit difficult to piece things together. especially when given code examples. I would’ve benefitted from seeing a full

waypoint.hclfile and a full Nomad jobspec in thenomad-jobspecexample, for instance.

Conclusion

We have covered a lot today, so give yourself a pat on the back! You survived my long-ass blog post! Here are the highlighs:

- We learned what Waypoint does

- We installed Waypoint in the HashiQube Vagrant VM

- We deployed a sample project (group of apps) using Waypoint

Waypoint is a great first step by HashiCorp to provide a Nomad-native tool that manages deployments to Nomad. Heck — there are no other Nomad-native tools that even do this. While Spinnaker has a Nomad plugin which enables you to deploy apps to Nomad, it doesn’t run natively on Nomad. I can’t, however, speak for how Spinnaker compares to managing Nomad deployments, as I haven’t had a chance to play with it (yet).

Waypoint has a lot of potential to be a kick-ass deployment management tool. Will it give your SRE team the super-holistic view of app deployments? Not at the moment. The pickings are slim in the deployment management space for Nomad. It’s nice to see that HashiCorp is investing in this space for its own container orchestrator (Nomad), and not just in Kubernetes. Seeing how much work that HashiCorp has put into growing this product since its initial release in 2020, I’d say that the future is promising. I’m excited to see what the next release of Waypoint holds in store!

I will now reward you with a photo of a snowy yak.

Peace, love, and code.

Related Reading

Be sure to check out my other articles in the Just-in-Time Nomad series!

https://adri-v.medium.com/just-in-time-nomad-80f57cd403ca

https://adri-v.medium.com/just-in-time-nomad-running-traefik-on-hashiqube-7d6dfd8ef9d8

Acknowledgements

Big thanks to the following folks for your continued support:

- My team of engineers on my Platform team — you’ve let me pick your brains and have made a Nomad lover out of this Kubernetes gal.

- riaan Nolan for your support and encouragement, and for your amazing work on HashiQube!

- The Hashi community, for featuring my posts!

- My dear readers, who continue coming back for more content! ❤️

References

- CI/CD tools which integrate with Nomad

- Installing Waypoint

- Waypoint Built-in Plugins

- Waypoint Input Variables

- Waypoint Nomad Job Plugin

- Waypoint Git Integration

- HashiCorp Waypoint Examples Repo on GitHub

- Waypoint App Promotion without re-build (Hashi forums)

- GitOps Workflow with Nomad (Hashi forums)

- Deleting projects on Waypoint (GitHub PR)

- Nomad On-Demand Runners for Waypoint (Hashi forums)

- Can’t Ping to Vagrant Box

Start blogging about your favorite technologies, reach more readers and earn rewards!

Join other developers and claim your FAUN account now!

Adriana Villela

@adrianamvillelaUser Popularity

63

Influence

6k

Total Hits

1

Posts

Only registered users can post comments. Please, login or signup.